Hernia Mesh Lawsuit Introduction

The American Medical Association now reports that the long-term risks of all hernia mesh implants may outweigh their benefits. A number of studies have also found that the complication rate for certain mesh products is shockingly high. As a result, thousands of injured patients and their families have filed claims against hernia mesh manufacturers seeking compensation for the pain, disfigurement and time lost because of mesh complications. If you are interested in seeing if you qualify for a potential Hernia Mesh lawsuit, please fill out the form below and one of our attorney’s will be in contact with you shortly.

Hernia Mesh Background

The American Medical Association now reports that the long-term risks of all hernia mesh implants may outweigh their benefits. A number of studies have also found that the complication rate for certain mesh products is shockingly high. As a result, thousands of injured patients and their families have filed claims against hernia mesh manufacturers seeking compensation for the pain, disfigurement and time lost because of mesh complications.

Hernias occur when an organ such as the intestines, pushes through the muscle or tissue that holds it in the correct place. Hernias can appear anywhere in a person’s abdominal wall, including the groin, belly-button or anywhere along your stomach. Hernias by themselves may cause no symptoms. When this is the case, your doctor may choose to monitor a hernia if it is not causing significant pain or enlarging instead of performing surgery.

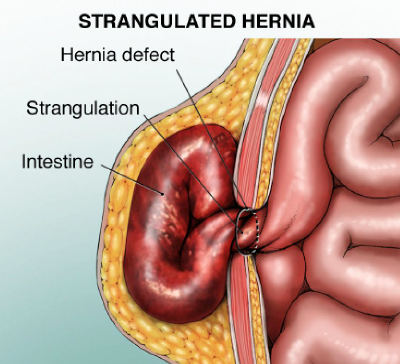

Some hernias are at risk of becoming strangulated, where the intestines twist and cut off the blood supply. A strangulated hernia is considered a medical emergency and needs immediate attention.

Symptoms of a strangulated hernia include: a sudden increase in pain, a change in the hernia’s color, nausea or vomiting, or the inability to move your bowels. If you experience any of these symptoms while you have a hernia you should seek immediate emergency medical attention.

Ultimately, surgery is the only treatment that can repair a hernia or a previously repaired hernia that has reherniated. Doctors perform nearly one million hernia repairs each year in the United States.

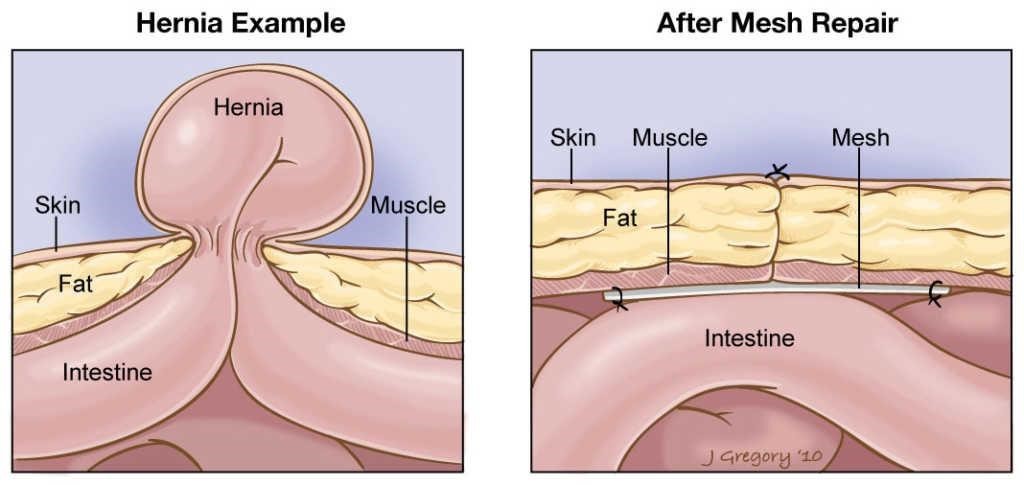

Surgical meshes are thin medical devices that are implanted in a person’s body, usually the abdominal cavity, to repair and strengthen the damaged tissue. The mesh also serves as a barrier to prevent further organ protrusion. Some studies have shown that surgeries using mesh lead to fewer hernia recurrences, others have found that the surgeries are linked to more frequent complications than mesh free repairs. A patient’s likelihood of developing complications may depend in part on the type of mesh implanted

Types of Hernia Meshes

Today, there are 3 main types of hernia meshes and each type of mesh can be considered either Absorbable or Non-Absorbable. You should keep in mind that there is no one type of mesh that has been linked to less complications than others. There have been histories of complications and lawsuits related to multiple devices.

Absorbable Mesh

Absorbable mesh will degrade and lose strength over time and are not used to provide long-term reinforcement to the repaired hernia. “As the material degrades, new tissue growth is intended to provide strength to the repair,” according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Absorbable meshes generally contain Dexon or Vicryl and are designed to be completely degraded over time. The benefits of absorbable mesh are that if successful, the patient will no longer have a permanent implant.

Non-Absorbable Mesh

Non-absorbable mesh implants, are considered permanent implants and will remain in the patient’s body unless they require a revision surgery. Non-absorbable mesh is intended to provide lasting reinforcement to the repair site and are generally designed to grow within the patient’s tissue.

Synthetic Mesh

Synthetic Mesh are nonabsorbable. This means they do not break down in a person’s body and are there forever unless a revision or replacement surgery is required. They are usually made out of polypropylene and a polyester or an ingredient called PTFE. These synthetic meshes contain only their synthetic material with no other additives. Many of the mesh at issue in current litigation are synthetic.

Polypropylene

Polypropylene is the most common synthetic material used in hernia mesh. Studies have shown that polypropylene mesh quickly incorporates into the anterior abdominal wall within 2 weeks of implantation. However, polypropylene is known to trigger inflammation when exposed to tissue. The inflammatory reaction may increase the patient’s likelihood of adhesion formation and result in contraction of the mesh and surrounding tissues. Researchers conjecture that this inflammatory reaction is contributes to postoperative pain and loss of elasticity. Polypropylene is also the same material used in the vaginal mesh products that have been the subject of tens of thousands of lawsuits. During that time, the FDA issued a number of warnings on the use of polypropylene mesh for procedures involving pelvic organ prolapse. We’re now seeing the same issues and awareness in the medical community with polypropylene used in hernia mesh products.

While the inflammatory response caused by polypropylene has an impact on the mesh’s durability, it also increases adhesion formation when the mesh is used next to the patient’s intestines. As a result, most polypropylene mesh contain an additional synthetic or biological material. Polypropylene may be combined with either a temporary or permanent material to reduce the likelihood of tissue adhesion or isolate the mesh from contact with the bowel. Some manufacturers line their mesh with substances such as poliglecaprone, carboxy-methylcellulose, titanium, or fish oil (omega-3 fatty acid). These materials are meant to isolate the polypropylene from the patient’s bowel and internal organs during the postoperative period. Unfortunately, these substances pose their own risk while a patient is recovering from hernia surgery. Additionally, when these barrier substances are absorbed or dissipate, the bowel is exposed to bare polypropylene.

The body’s inflammatory response to polypropylene causes the mesh to shrink by 30 to 50%. In addition to causing separation with the native tissue, this contraction can lead to the mesh rolling or twisting and therefore, exposing the polypropylene component to the bowel surface. The time it takes for polypropylene to cause these complications can be as soon as a couple days after surgery and upwards to years after the initial implant.

Although polypropylene mesh has been used since 1959, the material is not fit for implanting in people. Even the warning printed on bulk polypropylene supplies (the same material later used to make mesh) specifically warns that it is not to be used for permanent implants in people.

Polyester

Polyester is a carbon-based polymer frequently used in fabrics. Early studies raised concerns about polyester having a higher infection, small bowel obstruction, hernia recurrence, and fistula rates compared with other synthetic materials. Polyester meshes continue to be clinically available, with the caveat that they should be separated from the surface of the bowel. Polyester may offer some advantages over polypropylene. In an animal model of ventral hernia repair, a polyester mesh coated with a collagen hydrogel matrix (Parietex) showed superior incorporation into tissue than a composite mesh of polypropylene and sodium hyaluronate/carboxymethylcellulose (Sepramesh, Bard, Davol, Inc., Warwick, RI).

Expanded Polytetrafluoroethylene

Expanded polyttrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) is a woven mesh with small pores that was originally used in vascular grafts. The material used in abdominal cases generally has two sides—one side is smooth with very small pores, the other has larger pores with ridges and groves. The material is designed to place the smooth side toward the bowel to minimize adhesions, and the rough side toward the fascia to allow for tissue ingrowth. However, experimental studies have shown limited ingrowth of fibers and minimal inflammatory changes surrounding ePTFE grafts. This may be a result of small pore size, hydrophobicity, or the electronegative charge of the mesh.

In one study of ventral hernias, mesh made with ePTFE were compared with polypropylene based mesh. While the ePTFE mesh had fewer adhesions, there was no ingrowth of fibrocollagenous tissue into the ePTFE graft—leaving the mesh at risk to twist or move within the abdominal cavity. The polypropylene mesh was completely incorporated. In addition, hernia recurrence was 60% in the ePTFE group, compared with 0% in the polypropylene group. All of the recurrent hernias were at the junction of the mesh and the native tissue, suggesting that the lack of ingrowth into the ePTFE resulted in insufficient growth of the mesh to the fascia. A similar animal study compared ePTFE mesh (Dualmesh) with a composite mesh of polypropylene and sodium hyaluronate/carboxymethylcellulose (Sepramesh). There was no significant difference in adhesion formation or strength of incorporation. However, the ePTFE mesh had significantly more shrinkage in size (50.8 vs. 32.6%).

Biologic or Animal-Derived Meshes

These meshes are made out of biological material including horse and pig skin or intestine. Some biologics are made out of cow fetus skin as well. The characteristics of each biologic mesh are unique and dependent on the tissue source and the specific methods used to remove the donor tissue, leaving a collagen matrix, and sterilize the graft. The biochemical changes in the collagen structure that take place as a result of processing influences the biocompatibility, foreign body response, and immunogenic potential of the graft.

Composite Meshes

There are more than a dozen composite meshes made by different manufacturers. Physiomesh and C-QUR are two of the common composite meshes. Johnson & Johnson manufactures Physiomesh and Ethicon manufactures C-Qur.

Composite meshes combine multiple materials. They are marketed as providing the best of both synthetic and biologic meshes. In composite meshes, the side of the mesh that is attached to the abdominal wall is supposed to incorporate tissue from the abdomen. In addition, the mesh is tacked to the abdominal wall itself.

On the opposite side of the mesh, the product is coated with a biologic product, often omega 3 fatty acids, more commonly known as “fish oil” which triggers an allergic response in some people. Composite mesh manufacturers claimed that this coating of biologic oil would prevent the intestines that press up against the mesh from adhering and growing into the mesh.

Image of Zenapro (Cook Medical, Inc., Bloomington, IN), a hybrid made up of porcine small intestinal submucosa encasing a lightweight macroporous polypropylene mesh.

Studies on Hernia Mesh Complications

Several studies have found that patients who had a hernia mesh implanted during hernia repair may be at an increased long-term risk of experiencing complications. These complications may result in patients requiring additional treatment or surgeries years after their initial hernia repair.

A October 2017 study in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons called for a standardized labeling system for hernia mesh. The researchers found essential information missing from a wide variety of mesh products. For example, only 1 in 10 labels listed the mesh’s thickness.

“We found that food labels undergo critical scrutiny and detailed specifications, yet medical devices are not subjected to similar guidelines,” the authors wrote.

A 2016 study published in the journal Hernia looked at the long-term rate of MRSA infection among 632 hernia repair patients. MRSA is an antibiotic-resistant strain of staph infection. Researchers found 31 percent of patients experienced surgical-site infections within two years of surgery and 9.8 percent required medical intervention.

A 2015 study published in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons looked at 768 hernia mesh patients. Overall, 10 percent of the patients developed a hernia mesh infection within 30 days of surgery. Seven percent of those in the study tested positive for an MSRA infection somewhere other than the surgical site prior to their surgery, but of that group, 33 percent suffered a hernia mesh infection.

According to a 2014 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, using mesh led to a “small reduction” in the chance of ventral hernia recurrence compared to just stitching the torn tissue closed, but mesh also led to an increased risk of seroma and surgical site infection (SSI).

An October 2013 study in the Indian Journal of Surgery found “no statistically significant difference” between newer composite meshes and more traditional polypropylene meshes when it came to “adhesions, infection, intestinal fistulization, sinus formation, seroma and recurrence.”

In August 2012, researchers writing in the journal Surgical Infections said polypropylene surgical mesh for hernia repair was “unsuitable for intra-abdominal placement because of its tendency to induce bowel adhesions.”

In a 2016 study published in JAMA Surgery and presented at the 2016 Clinical Congress of the American College of surgeons found that mesh patients suffered more major complications and were more likely to require additional surgeries.

While in general, implanting a hernia mesh resulted in a lower risk of hernia recurrence, those benefits were off-set by “a risk of long-term mesh-related complications for open and laparoscopic mesh repairs.” Of the study’s initial 3,242 participants, 1050 required additional abdominal surgery or 32%. Also, the total amount of patients who ultimately required a surgery is likely higher as the study only examined complications up to 5-years of the initial implant.

In addition to a high percentage of revision and removal surgeries. Many patients suffered other complications including chronic pain, infections, open wounds that required the use of wound-vacuum, organs fused together and bowel adhesions.

In 2016 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) acknowledged the fact that mesh products were associated with a high occurrence of complications. The agency’s investigation of the mesh related medical adverse event reports, found the surgical patches to be the leading cause of obstruction and bowel perforation. The FDA claimed that most products involved were “no longer on the market” since the manufacturers voluntarily withdrew them from the market. Bard, for example, voluntarily recalled its Composix Kugel Mesh Patch in 2007 after facing three thousand lawsuits filed by patients. Bard ultimately paid $184 million to settle these lawsuits.

Another preclinical study conducted in rats found a 50% mesh reduction in size and instances of the implant folding and curling. At least one Clinical trial involving the Physiomesh was terminated early, potentially due to the incidence of serious adverse events experienced by human patients. However, the company continued to sell its hernia patch without reporting any results of the study to physicians, and only withdrew the product 10 months after trial results were published.

Studies Question the Long-Term Safety of Mesh

Patients undergo nearly 1,000,000 hernia repairs in the United States annually. Nearly all of those patients have a mesh implanted in them. Currently, there is disagreement among medical professionals as to whether the benefits of hernia repair with a mesh outweigh the possible increased risks of complications.

Dr. Kamal Itani of the VA Boston Healthcare System expressed the need to reevaluate long-held beliefs on the safety of using hernia mesh.

“[T]he risk–benefit ratio of mesh is not as clear as previously thought,” Itani wrote. “This calls into question the current practice of liberal use of mesh, even for repair of small hernias, when mesh is the norm for all incisional hernia repairs of any size. This finding supports previous calls to reconsider the use of mesh for smaller hernia defects.”

Other doctors have called attention to the lack of clinical trial data on most hernia mesh in the U.S. Under the Food and Drug Administratin’s medical device approval process, most hernia mesh that are currently on the market did not go through clinical trials before receiving approval.

When a hernia mesh manufacturer wants to bring a new product to the market, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s 510(k) premarket notification clearance process does not require that the manufacturer conducts clinical safety trials if the new mesh is “substantially similar” to a mesh that has already gone through the more rigorous approval process. This often results in mesh with experimental designs and substances becoming implanted in patients despite a lack of long-term safety data. In other words, the manufacturer is able to use patients as guinea-pigs instead of paying for safety studies.

As the 2016 study’s authors wrote “Demonstration of long-term safety is required for drugs in the United States but not for some devices, such as hernia meshes, which are not subject to similarly strict documentation. Thus, the complete spectrum for the risks and benefits of mesh used to reinforce hernia repair is not known because there are very few clinical trial data reporting hernia outcomes as they pertain to mesh utilization.”

Complications Related to Hernia Mesh include:

- Infections and Sepsis. Serious infected wounds relating to hernia mesh may require the removal of the mesh. This is a very dangerous injury as severe infections may lead to death.

- Mesh Rejection. In some cases the patient’s body may not accept the implanted mesh. This can cause complications such as infection, seroma or reopening of the wound and require that the mesh be removed and re-repaired with another type of surgery or hernia mesh.

- Bowel Obstructions. If the mesh adheres to patient’s bowel, they may be unable to defecate. Constipation may indicate there is a possible obstruction. If you suspect a bowel obstruction you should seek medical care quickly.

- Adhesions. Some types of mesh have been reported to attach to the patient’s bowel, stomach or other organs.

- Migration and Shrinkage. Mesh can move, twist, flip and shrink inside of the patient. Mesh that migrates can cause pain and form hard masses. For mesh that have a different coating on one side, a twisted or flipped mesh can cause additional inflammation if the abdomen facing side turns to the patient’s organs.

- Organ Perforation. In some instances a migrated, twisted or hardened mesh can puncture internal organs.

- Chronic abdominal pain. Chronic pain may indicate a number of underlying complications such as tissue migration, adhesions, inflammation and infection.

Hernia Mesh FDA Recalls and Manufacturer Withdrawals

The FDA has announced several hernia mesh recalls. The agency also issued a Safety Communication in 2014 to warn the public about complications linked to hernia mesh.

Some recalls were for packaging errors, but others were for high failure rates ands reports of adverse events. Companies who issued recalls of their hernia mesh products include Atrium Medical Corporation, Bard Davol and Ethicon.

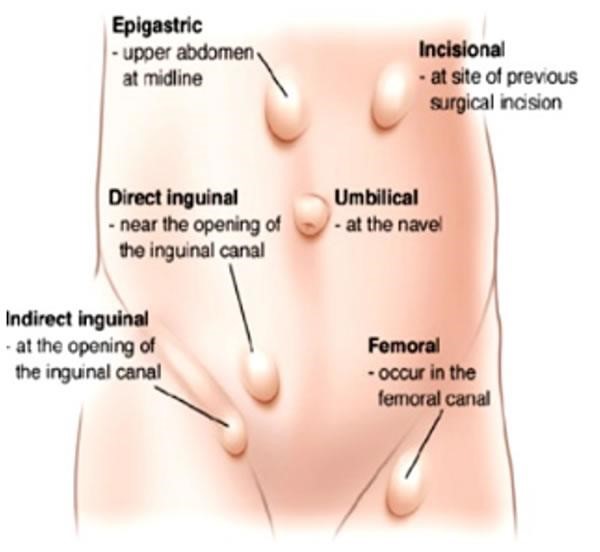

Types of Hernia

There are several types of common hernias.

Groin (inguinal) hernia: These are the most common hernias and occur more often in men. These hernias appear as a bulge in the groin area where the skin of the thigh joins the torso.

Femoral hernia: The femoral canal is the path that the femoral artery leaves the abdominal cavity to enter the thigh. Sometimes this space enlarges enough to allow abdominal contents (usually intestine) to protrude into the canal. A femoral hernia causes a bulge just below the crease in the middle of the upper leg. Femoral hernias are particularly dangerous because they have a high risk of cutting off blood supply.

Umbilical Hernias: These hernia often appear at birth as a protrusion at the belly button (the umbilicus). An umbilical hernia is caused when an opening in the child’s abdominal wall, which normally closes before birth, doesn’t close completely. Larger hernias and those that do not close by themselves usually require surgery when a child is 2 to 4 years of age. Umbilical hernias can also appear later in life because this spot may remain a weaker place in the abdominal wall.

Surgical Hernias: Abdominal surgery can create an area of weakness through which a hernia may develop. This occurs after 2%-10% of all abdominal surgeries, although some people are more at risk. Even after surgical repair, incisional hernias may return.

History of Hernia Repair

Hernia treatments have a long history of surgical and non surgical treatments before the use of mesh. Doctors may perform hernia repair surgery with or without mesh. Hernia repair surgery with mesh is called hernioplasty; without mesh it is called herniorrhaphy.

Mesh free hernia repairs have been performed successfully for over 100 years. Between 1883 and 1889 Italian surgeon Edoardo Bassini performed 270 inguinal hernia repairs using a mesh free durable repair technique he developed. Bassini tracked the outcome of his patients over 5 years and identified 8 recurrences out of the original 270 (4%).

In 1945, the Shouldice clinic in Toronto opened and began practicing a technique that bears the same name. Similar in nature to the repair initially described by Bassini, the Shouldice clinic reports a 1% hernia recurrence rate with very close follow up.

Beginnings of Hernia Repairs with Mesh

Throughout the 20th century various techniques using a reinforcement material (mesh) to repair inguinal hernias were developed. In the 1900s various forms of woven soft metal grafts were used and found to be unsatisfactory. In 1935 Wallace Carothers, a chemist at Dupont, discovered a method to create synthetic polymers and is credited with the creation of Nylon. The “era of plastics” was ushered in and other polymers like polyester and polypropylene were discovered and used in the manufacture of countless items including surgical mesh.

The 1940s marked the beginning of synthetic polymers used in inguinal hernia repair. By the 1960s, Dr Richard Newman had performed over 1600 inguinal hernia repairs using polypropylene.

Since the 1980s, there has been an increase in mesh-based hernia repairs. By 1989, surgeons were using less invasive laparoscopic surgery with mesh in hernia repairs. By 2000, non-mesh repairs represented less than 10 percent of groin-hernia-repair techniques. Today, hernia repair with synthetic mesh is the most common procedure and very few patients undergo a mesh-free hernia repair.

Surgical mesh acts as scaffolding to repair muscle walls and prevent organs from coming through. After placing the mesh over the hernia defect, doctors use stitches, tacks or surgical glue to hold the mesh in place. Over time, the patient’s tissue should grow into the small pores in the mesh and strengthen the muscle wall. Most mesh repairs are permanent, meaning the implant remains in the body for the rest of the patient’s life.

Types of Hernia Repair

Open Repair

There are two types of hernia repair. “Open” repair is where the surgeon makes a incision over the hernia site and places a mesh. This incision can be large if the hernia itself is large. Often called “tension free” the mesh is placed over the defect and there is a closure performed by the surgeon with the intent of the mesh gain to grow within the tissue.

Laparoscopic Repair

The other type of hernia repair is “laparoscopic.” Laparoscopic is often marketed as less invasive. Typically, the surgeon will make several small incisions and place a scope within the belly button. The scope will have a camera and light to allow the surgeon to perform the surgery. The surgeon will inflate the abdomen with carbon dioxide and then mesh is then inserted through a small incision. The surgeon will use 2 incisions to affix the mesh.

In some cases, complications during a laparoscopic procedure will require the surgeon to open the patient, resulting in a larger scar and prolonged recovery.

Mesh Free Hernia Surgeries

While most hernia repairs involve mesh, there are several alternatives. About 10 percent of hernia repairs in the U.S. are still done without hernia mesh, generally falling into one of five techniques — the oldest of which dates back to the 1880s. These techniques include:

BASSINI REPAIR

Edoardo Bassini pioneered hernia repair surgical techniques. In 1884, he created a technique that is still used in mostly developing countries. The technique is referred to as “tension repair” because it places tension on muscle tissues around the hernia.

MCVAY/COOPER’S LIGAMENT

In the early 20th century, this technique was developed to improve on the success rate of the Bassini repair. With the McVay/Cooper technique, the patient’s tissue is sutured to the Cooper’s ligament. The technique was successful in repairing large hernias.

SHOULDICE REPAIR

The Shouldice technique was developed during the 1940’s and is the most common mesh free hernia repair procedure. It is considered more complicated but effective when done by a skilled surgeon. In this type of repair, three layers of muscle and tissue are cut. The surgeon then places the patient’s intestines and any fatty tissue that passed through the opening back into the abdomen. Each of the three layers is then individually stitched closed so that it overlaps the deeper layer. This overlapping pattern reinforces the abdominal wall.

The Shouldice repair has a high success rate and low hernia recurrence rate when performed by a skilled surgeon. It’s estimated that a surgeon must complete several hundred procedures in order to become competent in the technique.

DESCARDA REPAIR

The Descarda hernia repair technique is a tension-free procedure — that is, it places no tension on muscle or other tissue. First presented in 2001, the Descarda repair involves suturing a strip of a patient’s own muscle (the external oblique aponeurosis) to another muscle (the internal oblique muscle) and to the inguinal ligament. A 2012 study of 200 male patients found the results three years after surgery were similar to those of men receiving traditional open surgery using mesh — the Lichtenstein technique.

GUARNIERI REPAIR

The Guarnieri repair, first used in 1988, is another tension-free technique that can be performed with or without mesh. It involves altering the physiology of the patient’s inguinal canal by overlapping the external oblique aponeurosis – the same muscle involved in the Descarda repair — in a “double-breast” fashion.